Ohm's law states that the

current through a conductor between two points is directly

proportional to the potential difference across the two points. Introducing the constant of proportionality, the

resistance,

[1] one arrives at the usual mathematical equation that describes this relationship:

[2]

where

I is the current through the conductor in units of

amperes,

V is the potential difference measured

across the conductor in units of

volts, and

R is the

resistance of the conductor in units of

ohms. More specifically, Ohm's law states that the

R in this relation is constant, independent of the current.

[3]

The law was named after the German physicist

Georg Ohm,

who, in a treatise published in 1827, described measurements of applied

voltage and current through simple electrical circuits containing

various lengths of wire. He presented a slightly more complex equation

than the one above (see History section below) to explain his experimental results. The above equation is the modern form of Ohm's law.

In physics, the term

Ohm's law is also used to refer to various generalizations of the law originally formulated by Ohm. The simplest example of this is:

where

J is the

current density at a given location in a resistive material,

E is the electric field at that location, and

σ is a material dependent parameter called the

conductivity. This reformulation of Ohm's law is due to

Gustav Kirchhoff

In

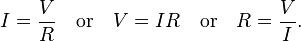

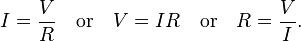

circuit analysis, three equivalent expressions of Ohm's law are used interchangeably:

Each equation is quoted by some sources as the defining relationship of Ohm's law,

or all three are quoted,

or derived from a proportional form,

or even just the two that do not correspond to Ohm's original statement may sometimes be given.

The interchangeability of the equation may be represented by a triangle, where V (

voltage) is placed on the top section, the I (

current) is placed to the left section, and the R (

resistance)

is placed to the right. The line that divides the left and right

sections indicate multiplication, and the divider between the top and

bottom sections indicates division (hence the division bar).

Resistive circuits

Resistors

are circuit elements that impede the passage of electric charge in

agreement with Ohm's law, and are designed to have a specific resistance

value

R. In a schematic diagram the resistor is shown as a

zig-zag symbol. An element (resistor or conductor) that behaves

according to Ohm's law over some operating range is referred to as an

ohmic device (or an

ohmic resistor) because Ohm's law and a single value for the resistance suffice to describe the behavior of the device over that range.

Ohm's law holds for circuits containing only resistive elements (no

capacitances or inductances) for all forms of driving voltage or

current, regardless of whether the driving voltage or current is

constant (

DC) or time-varying such as

AC. At any instant of time Ohm's law is valid for such circuits.

Resistors which are in

series or in

parallel

may be grouped together into a single "equivalent resistance" in order

to apply Ohm's law in analyzing the circuit. This application of Ohm's

law is illustrated with examples in "

How To Analyze Resistive Circuits Using Ohm's Law" on

wikiHow.

Reactive circuits with time-varying signals

When reactive elements such as capacitors, inductors, or transmission

lines are involved in a circuit to which AC or time-varying voltage or

current is applied, the relationship between voltage and current becomes

the solution to a

differential equation,

so Ohm's law (as defined above) does not directly apply since that form

contains only resistances having value R, not complex impedances which

may contain capacitance ("C") or inductance ("L").

Equations for

time-invariant AC circuits take the same form as Ohm's law, however, the variables are generalized to

complex numbers and the current and voltage waveforms are

complex exponentials.

[26]

In this approach, a voltage or current waveform takes the form

, where

t is time,

s is a complex parameter, and

A is a complex scalar. In any

linear time-invariant system, all of the currents and voltages can be expressed with the same

s

parameter as the input to the system, allowing the time-varying complex

exponential term to be canceled out and the system described

algebraically in terms of the complex scalars in the current and voltage

waveforms.

The complex generalization of resistance is

impedance, usually denoted

Z; it can be shown that for an inductor,

and for a capacitor,

We can now write,

where

V and

I are the complex scalars in the voltage and current respectively and

Z is the complex impedance.

This form of Ohm's law, with

Z taking the place of

R, generalizes the simpler form. When

Z is complex, only the real part is responsible for dissipating heat.

In the general AC circuit,

Z varies strongly with the frequency parameter

s, and so also will the relationship between voltage and current.

For the common case of a steady

sinusoid, the

s parameter is taken to be

, corresponding to a complex sinusoid

.

The real parts of such complex current and voltage waveforms describe

the actual sinusoidal currents and voltages in a circuit, which can be

in different phases due to the different complex scalars.

Linear approximations

Ohm's law is one of the basic equations used in the

analysis of electrical circuits. It applies to both metal conductors and circuit components (

resistors)

specifically made for this behaviour. Both are ubiquitous in electrical

engineering. Materials and components that obey Ohm's law are described

as "ohmic"

which means they produce the same value for resistance (R = V/I)

regardless of the value of V or I which is applied and whether the

applied voltage or current is DC (

direct current) of either positive or negative polarity or AC (

alternating current).

In a true ohmic device, the same value of resistance will be

calculated from R = V/I regardless of the value of the applied voltage

V. That is, the ratio of V/I is constant, and when current is plotted as

a function of voltage the curve is

linear (a straight line). If

voltage is forced to some value V, then that voltage V divided by

measured current I will equal R. Or if the current is forced to some

value I, then the measured voltage V divided by that current I is also

R. Since the plot of I versus V is a straight line, then it is also true

that for any set of two different voltages V

1 and V

2 applied across a given device of resistance R, producing currents I

1 = V

1/R and I

2 = V

2/R, that the ratio (V

1-V

2)/(I

1-I

2)

is also a constant equal to R. The operator "delta" (Δ) is used to

represent a difference in a quantity, so we can write ΔV = V

1-V

2 and ΔI = I

1-I

2.

Summarizing, for any truly ohmic device having resistance R, V/I =

ΔV/ΔI = R for any applied voltage or current or for the difference

between any set of applied voltages or currents.

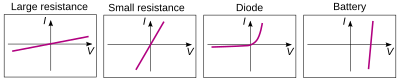

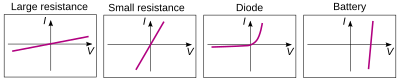

The

I–V curves of four devices: Two

resistors, a diode, and a battery. The two resistors follow Ohm's law: The plot is a straight line through the origin. The other two devices do

not follow Ohm's law.

There are, however, components of electrical circuits which do not obey Ohm's law; that is, their relationship between current and voltage (their I–V curve) is nonlinear (or non-ohmic). An example is the p-n junction diode (curve at right). As seen in the figure, the current does not increase linearly with applied voltage for a diode. One can determine a value of current (I) for a given value of applied voltage (V) from the curve, but not from Ohm's law, since the value of "resistance" is not constant as a function of applied voltage. Further, the current only increases significantly if the applied voltage is positive, not negative. The ratio V/I for some point along the nonlinear curve is sometimes called the static, or chordal, or DC, resistance,but as seen in the figure the value of total V over total I varies depending on the particular point along the nonlinear curve which is chosen. This means the "DC resistance" V/I at some point on the curve is not the same as what would be determined by applying an AC signal having peak amplitude ΔV volts or ΔI amps centered at that same point along the curve and measuring ΔV/ΔI. However, in some diode applications, the AC signal applied to the device is small and it is possible to analyze the circuit in terms of the dynamic, small-signal, or incremental resistance, defined as the one over the slope of the V–I curve at the average value (DC operating point) of the voltage (that is, one over the derivative of current with respect to voltage). For sufficiently small signals, the dynamic resistance allows the Ohm's law small signal resistance to be calculated as approximately one over the slope of a line drawn tangentially to the V-I curve at the DC operating point.

Seorang pemuda yang hidup di Perth telah sampai usia saat ia merasa harus mencari pasangan hidup. Jadi ia mencari-cari gadis sempurna di seluruh negeri untuk dinikahi. Setelah berhari-hari, berminggu-minggu mencari, ia bertemu dengan gadis yang sangat cantik-jenis gadis yang bisa menghiasi sampul majalah perempuan bahkan tanpa make-up atau kosmetik!

Seorang pemuda yang hidup di Perth telah sampai usia saat ia merasa harus mencari pasangan hidup. Jadi ia mencari-cari gadis sempurna di seluruh negeri untuk dinikahi. Setelah berhari-hari, berminggu-minggu mencari, ia bertemu dengan gadis yang sangat cantik-jenis gadis yang bisa menghiasi sampul majalah perempuan bahkan tanpa make-up atau kosmetik! Seorang pemuda yang hidup di Perth telah sampai usia saat ia merasa harus mencari pasangan hidup. Jadi ia mencari-cari gadis sempurna di seluruh negeri untuk dinikahi. Setelah berhari-hari, berminggu-minggu mencari, ia bertemu dengan gadis yang sangat cantik-jenis gadis yang bisa menghiasi sampul majalah perempuan bahkan tanpa make-up atau kosmetik!

Seorang pemuda yang hidup di Perth telah sampai usia saat ia merasa harus mencari pasangan hidup. Jadi ia mencari-cari gadis sempurna di seluruh negeri untuk dinikahi. Setelah berhari-hari, berminggu-minggu mencari, ia bertemu dengan gadis yang sangat cantik-jenis gadis yang bisa menghiasi sampul majalah perempuan bahkan tanpa make-up atau kosmetik!

, where t is time, s is a complex parameter, and A is a complex scalar. In any

, where t is time, s is a complex parameter, and A is a complex scalar. In any

, corresponding to a complex sinusoid

, corresponding to a complex sinusoid  .

The real parts of such complex current and voltage waveforms describe

the actual sinusoidal currents and voltages in a circuit, which can be

in different phases due to the different complex scalars.

.

The real parts of such complex current and voltage waveforms describe

the actual sinusoidal currents and voltages in a circuit, which can be

in different phases due to the different complex scalars.